What is grain direction in wood?

When approaching timber as a bulk material, it can be easier to just think of it as a solid, cohesive object. A piece of wood is just that: a single piece. However, once we start working on the timber and making or manufacturing things, the internal structure of the timber not only becomes more apparent, but is essential to keep in mind for the best and most beautiful results.

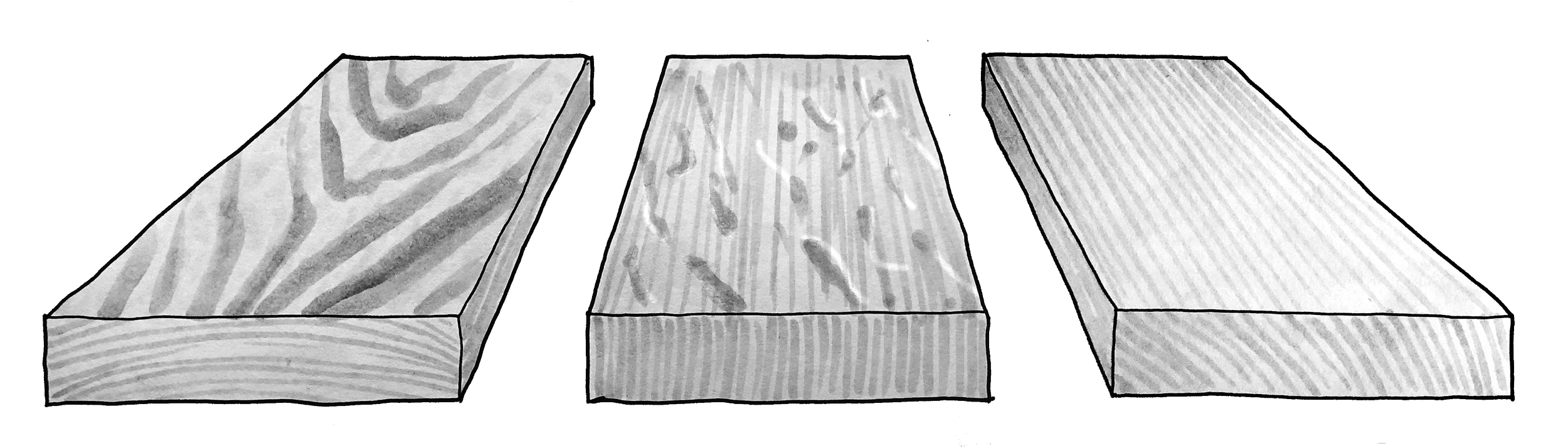

The most noticeable characteristic of timber is its grain - the lines that run in different directions along the surface, sides, and ends of a board. As you can see in the illustration below, depending on how the board was cut from the log, the grain may appear straight and parallel, or curvy and wavy.

From left to right: Plain sawn, quarter sawn, and rift sawn timber boards.

We can describe what part of the grain we’re talking about with a few key terms:

End grain: often the shortest and thinnest side of a board, this is the part of a board that would be facing up or down if you located it back inside of a tree. End grain can be harder to work or cut because all of the layers of grain are stacked together and have to all be cut through.

Long grain: The sides and faces of a board, where the timber grain runs along the length of the board. If you want to get specific, these can be divided further into:

Face grain: The grain along the wider two surfaces.

Edge grain: The grain along the thinner two surfaces.

These terms may differ regionally and between different woodworkers, but however we describe them we’re trying to understand the same thing: where exactly on the board we’re talking about, and how the grain is interacting with that surface.

Why does grain matter?

The grain of a board can be understood as the growth layers of a tree – often these are seen as rings if you look at a circular segment of a cut tree, but these rings run from bottom to top of every part of the tree that is the same age. These rings are often described as early wood and late wood, or seasonal rings, as they are demarcated by different seasons the tree experiences. These rings often align with an annual seasonal calender, which is how they can be used to find the approximate age of a tree, but can be affected by other things like unusual weather events, natural disasters, pests and other animals, or human interaction with trees.

As a tree is growing, the outer-most layer moves nutrients and liquid up and down the tree to where it’s needed, and then each successive year a new layer is grown and the tree gets larger. Because of the way these layers grow, timber can be easier or harder to work depending on the direction and angle we are using our tools. This grain also will look different depending on how it meets the display surfaces, resulting in very different lines and patterns, some of which are highly desirable and others which look very ordinary.

Working with or against the grain

You may have heard the terms working “with” or “against” the grain, or just heard colloquial phrases including those words. As woodworkers, we become intimately acquainted with how grain affects our work processes, and how to read and work with grain to get the most out of our timber and tools.

When we’re thinking about working with the grain, have a look at the side of your piece of wood. If the grain isn’t perfectly parallel to your work surface, the lines will come up and meet your work face in little points. The direction these points are, well, pointing is the direction of the grain.

Some boards have nice, even grain that’s all pointing in the same direction, but because timber is a natural material, that’s not always the case! Sometimes the same face will have multiple grain directions, and so we have to be careful to use tools and approaches that best serve the grain and reduce the total potential tear out.

If you’re new to woodworking, get a bladed tool like a hand plane, drawknife or spokeshave, and try to work along the face of a board in different directions – you’ll notice that some directions feel easier to work, and others feel more difficult. That easy working feeling is what we want, and as you practice and get better, you’ll be looking to get that optimal feeling.

If you’re interested in learning more about grain in a hands-on way, or working with some beautiful hand tools, check out our courses!

Illustrations by Liz, © Among The Trees